Q&A with Tamara Dean

A Journey from 2D Photography to 3D Sculptural Art: Tamara Dean shares her experience at UAP during her Artist Residency in Brisbane, Australia.

While you have an extensive photographic practice, you have been experimenting with installation for many years. What prompted your explorations into sculpture and how did you find the experience of formalising your sculptural practice through this residency?

Tamara Dean (TD) I first began working with installation in 2015 with my multi-sensory work “Here-and-Now” which incorporated scent and sound into the viewers experience. My motivation was to build on the 2D photographic experience, to expand the viewers engagement with the work, using scent and sound to create a transportive element to the installation.

I began incorporating sculptural elements along with the scent, sound, moving -mage and installation components in my series “High Jinks in the Hydrangeas”, the inaugural exhibition to launch Ngununggula – Southern Highlands Regional Gallery.

This series was created in the wake of the 2019-20 bushfires – I began life casting my limbs, and incorporating assemblages of found object such a driftwood, fruit and coal. I loved the interplay between the photographic works and the sculptures within the gallery space. There is a beautiful sense of wonder in seeing elements move from the 2D photographic space into the 3D physical experience.

Being given the opportunity to engage in an artist residency with UAP was incredibly exciting for me as I had been wanting to continue developing sculptural components in my work, although hadn’t found an opportunity to fully investigate this potential.

I began my residency in the pattern-making department experimenting with forms and elements which were to be integrated in the sculpture I was designing, building a rough but effective model in terms of communicating its shape and thrust of energy.

I quickly realised that with the gravitational challenges I was asking of the model, UAP’s 3D modelling technology capabilities would further assist in designing the complex structure of the tornado that I had been working up to.

I worked very closely with John Nicholson and Nolan Cunningham through the digital programmes, and with their talent and support we were able to translate my ideas into the 3D space and design multiple iterations of the concept.

The 3D modelling systems have been a revelation for me in terms of translating visualisations and concepts conceived in my mind for years, and resolving them into tangible, physical, attainable models.

Did you have specific goals for the residency or conceptual starting points you planned to resolve? Were these goals achieved? Why / why not?

(TD) Yes, I came to the residency with a definitive concept I wanted to explore which we did to great effect.I can happily say that my goals were achieved, and I have to thank UAP for their generosity in channelling so many of their valuable resources into my project over the duration of the residency.

Working with UAP, you delved into modelling and manipulating forms in 3D rendering software. How did this process of working in 3D differ from capturing 2D photographs?

(TD) It really pushed me to consider the many planes/angles/aspects of the work when we were creating the large-scale sculpture. How it needed a mix of complex areas as well as areas which allowed the eye to rest. It was a similar process to the sense of intuition I rely on when working on my photographs. Just more complex in terms of considering the viewers experience of the sculpture.

Where did your interest in movement or transience originate and how did you find the process of translating movement into sculptural forms?

(TD) I think that simply the experience of being alive, of the constant change and movement of living is an element that is embedded within the works I create. And so this sense of ‘moving through’ is often represented in my work.

In my early career I worked as a newspaper photographer with the SMH for 13 years. In this role I would observe life in action, and I learnt to hone my eye and anticipate when elements and energies in motion would come together to culminate in a moment at which point I would be ready to take the photograph.

I think that this experience, the skills and instincts I developed in terms of watching and anticipating a moment within a whirlwind of elements in motion has had a profound effect on the work I continue to make today.

This idea of expressing the swirling, chaotic and unpredictable movement and energy of the tornado in my sculptural form has been key to the sculptural designs we have developed. From the very conception of this work, the energy of the moving tornado was a leading force in the design.

I enjoy working with an unresolved moment, a moment that asks the viewer “what is about to happen”? For me, this is a way I engage my audience to delve deeper into the work. To engage them to ask themselves what this work is about and how does it make them feel.

In terms of the tornado, I wanted it to defy gravity, to push forward and lurch out, creating a gravitational tension; the sculpture off-balance as a static form, although expressing a directional momentum which would feel natural if moving.

The drama in the sensation of imbalance, the physicality, form and scale are all elements which really excite me working with sculptural forms.

Your photographic works consistently hold a strong presence of the ‘subject’, how did you find the experience of ‘creating’ your subjects through 3D modelling and has this changed your relationship with the subjects of your work?

(TD) Whilst in my early photographic work there is a sense of character in my models, you may notice that many of the faces in my recent photographs are obscured. In recent years I have made a point of stripping back the human form to the figure rather than representing a person with an identity.

This is an intentional shift to use the figure to represent humanity, rather than depicting a specific person. To communicate my larger message that humans are part of nature.

So moving into the 3D modelling on the residency, I found it quite useful to be able to form up figures (some referenced from my underwater photographs), using only limbs (not faces) in the sculpture to imply the figure withing a swirling mass. It feels like a natural progression from my life cast limbs in “High Jinks in the Hydrangeas’’.

You were commissioned through UAP to create a digital video installation, Outside In, in 2019, what new experiences or ideas have emerged from working with UAP this time?

(TD) I have had the pleasure of working with UAP on my ‘Stream of Consciousness” installation which was part of the 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, as well as the digital video installation, Outside In, in 2019.

Both of these experiences gave me an insight into the ability to create cutting edge new work with UAP. I feel very grateful to have been given the opportunity to work with a number of members of the team, and feel that my ambitions expand when working in this collaborative atmosphere. You can’t really ask for more than that as an artist.

What was the most stimulating part of the residency and what impact has the experience of the residency had on your future artistic practice?

(TD) Working with John Nicholson and Nolan Cunningham in the 3D modelling blew my mind. It is as though a door has been opened, and now there is a channel/medium through which to translate the images and concepts from my mind into physical form. Truly exciting stuff.

I have no idea whether there will be another opportunity to continue developing my work down this path given that the expertise of the UAP team was key to this transition but should there be more opportunities that present themselves I can see great potential here.

Do you have any advice for emerging artists/photographers?

(TD) Just start, and then keep going. It sounds simple but that’s it, that’s the hardest part. By consistently creating work you will find your style/voice. Enter competitions. They are great in building confidence and getting your work out there on gallery walls, sometimes with artists who you admire.

Image Credit: Rachel See courtesy of UAP | Urban Art Projects

#Related Articles

Selfie Panda Goes Viral

Panda-mania materialized! A "Selfie Panda" sculpture by Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman debuted recently in the city of Dujiangyan in southwest China's Sichuan province, and may well become the new mecca for selfie and panda lovers alike.

Leonie Rhodes: Authenticity, Identity, and Connection Over Standing Out From the Crowd

An award-winning multidisciplinary artist and facilitator from South London, now working from Brisbane on unceeded Jagera and Turrbal land.

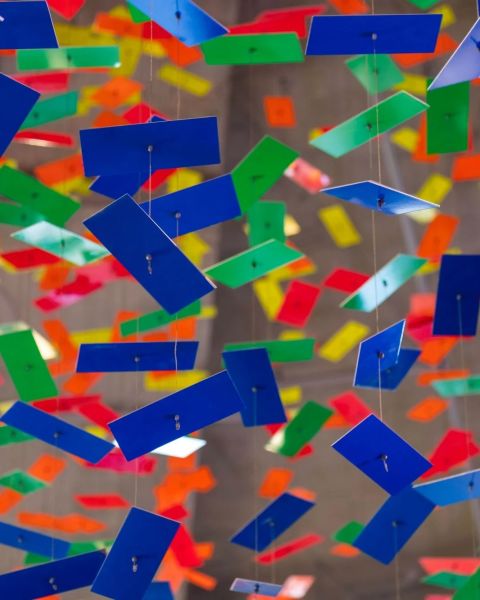

Design Robotics: ‘a Lifetime of Summers’ by Nike Savvas

An immersive and multi-colored sensorial experience was commissioned by Lendlease in 2019, as a permanent hanging art installation atop the ground floor of The Exchange – Sydney’s latest architectural icon and platform for creative innovation. Urban Art Projects (UAP) was instrumental throughout the design, fabrication and installation of this optically exquisite piece.