Five Questions with Elisa Jane Carmichael

Quandamooka woman and multi-disciplinary artist Elisa Jane Carmichael was born in Brisbane. Her works draw inspiration from her salt-water heritage and her connections to country, building upon a foundation of cultural knowledge and practice that has been passed down by her family.

Quandamooka woman and multi-disciplinary artist Elisa Jane Carmichael was born in Brisbane. Her works draw inspiration from her salt-water heritage and her connections to country, building upon a foundation of cultural knowledge and practice that has been passed down by her family. In celebration of her new work Water is Life, installed within Brisbane's South Bank, we sat down with Elisa to chat about her practice, inspirations and public art.

UAP: Can you describe what underpins your art practice, and the challenges and positives of stepping from the gallery into the public realm?

ELC: As a weaver, I work with various fibres, both natural materials from Country and contemporary materials such as ghost nets and recycled elements. The materials I choose to work within my practice form the story I am weaving. One of the challenges I work through stepping into public art is turning something fibrous, delicate, and sometimes ephemeral into something solid, long-standing and interactive. It’s really exciting to see the transformation of materials throughout this process.

You’re known for using traditional techniques to create your weaves, painting, and textiles, more recently experimenting with large-scale cyanotypes. What is your approach to creating contemporary works that still embrace traditional techniques and honour Country?

Thinking of the concept I’m sharing within my work leads me to the type of materials, techniques, and medium I will create in. Combining traditional materials and techniques with contemporary fibres and forms is a way to carry the stories from the past into the future honouring Country. Using cyanotype is a way for weaves, materials, and Country to create their own marks and fabrics.

Your recent work Water is Life is permanently installed beside the river at Brisbane’s South Bank. What do you hope the work communicates to the diverse audiences and population of Brisbane?

Water is Life is a reminder that we need to honour and protect our waterways as water provides us with a constant source of life and sustenance. The work also honours the waterways and the landscape of the area before colonisation. Always was, always will be Aboriginal land.

You’ve worked with Judy Watson on a few occasions assisting her during the making of tow row and more recently creating the Dilly Bag for nerung ballun (nerang river), freshwater, saltwater installed at HOTA on the Gold Coast. How did you first come to work with Judy and how has your creative relationship developed over the years?

In 2014 I participated in the first Gold Coast Artist camp on South Stradbroke island where Judy was the mentor. Since then we have become great friends and I feel very honoured to assist and work together with Judy.

What do you think the role of the artist is in public spaces?

All artists have their own approaches but I think for me I see art in public spaces as a reminder, acknowledgment or memory of an area that is important to be seen and recognised by the community.

#相关文章

First Nations artwork honouring the eel launched in Parramatta Square

Created by Kamilaroi artist, Reko Rennie, the 7.5-metre tall sculpture depicts two eels rising from the ground and crossing each other as they play.

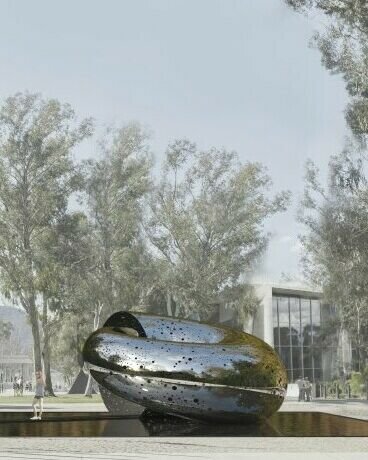

National Gallery of Australia announces major sculpture commission by Lindy Lee

To be built at our Brisbane workshop, 'Ouroboros' will be constructed from mirror-polished recycled and reclaimed stainless steel and weighing approximately 13 tonnes; it will be the largest acquisition and one of the most significant public art commissions ever in Australia.